In this article, Senior Paraplanner and Chartered Financial Planner, Warren Bentham, explains why cash might seem attractive now versus investments, but we’re unlikely to stay in this position forever and the rules of the game haven’t changed.

It is generally accepted that investors should hold a level of cash reserves that can be easily accessible as a contingency fund in case they experience a fall in income or a need to make a one-off emergency purchase. Investing too much of your liquid assets might mean that you need to encash some of your holdings at an unfavourable time, potentially leading to a loss or an unnecessary tax liability.

Historically, with interest rates having been so low, the returns available from cash were unappealing, and the threat of inflation eroding the real value of assets meant that investors were more willing to accept an element of risk in order to potentially achieve more favourable returns. Now, with interest rates available today of around 5.0%, why should investors continue to invest, especially when equity markets remain relatively volatile?

Three reasons for investing

Firstly, the threat of inflation still exists. Even taking into account the fall in the inflation rate over the previous 12 months from 6.7% in September to 4.6% in October, as measured by the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), this remains a high bar to exceed by any real margin using deposit accounts alone.

Secondly, it is worth remembering that while investment markets may look different today, the basic laws of capitalism have not changed. A concept we know in the financial planning world as the ‘Efficient Frontier’ shows the set of portfolios with the highest possible expected return based on a given level of risk, with the returns expected being higher the more risk that you were willing to take. So why is this?

Starting with the rate of interest that investors can receive from their bank, governments must offer a higher level of returns to tempt investors away from cash deposits, given the added level of risk that they would be exposed to, in order for the governments to borrow sufficient levels to meet their spending obligations. As companies who wish to borrow money from investors cannot offer the same level of security as a government can, they must incentivise investors to lend to them, and therefore are required to offer a higher potential rate of return than offered by the Government.

To consider an investment into equities, shareholders must expect to have the potential to generate a higher level of return than would be available from their bank, or from lending to the Government, or even lending to the company in which they are investing. As such, any new projects being reviewed within a firm that would not have the potential to provide a return in excess of interest rates should not be undertaken and over the long term company profit expectations should therefore exceed cash returns.

The bottom line is that cash sets the bar in terms of the level of returns required, and all alternative investment options then need to jump over this in order to be considered as viable.

Thirdly, while interest rates are currently higher than they have been for nearly two decades, the consensus is that we are now at, or near, the peak of the interest rate cycle, and we are therefore unlikely to see rates move any higher. A large proportion of economists and analysts actually expect that interest rates will fall again during 2024. As such, it is possible that the current level of deposit interest rates being received by investors will not be sustainable for the long term.

Finally, the time horizon for the proposed investment remains a critical factor. Over shorter time periods, cash may provide a higher level of returns and a hedge against inflation, but over longer time periods, cash tends to come off worse, even when inflation is relatively low.

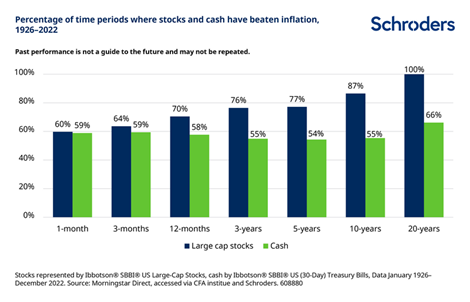

The chart below, provided by Schroders, shows the comparative level of returns from cash and equities over a range of timeframes, extracted from 96 years of data which is then set against inflation over the same relative timeframes:

This chart shows that over time periods of three months or less, there has not been much difference in the likelihood of cash or equity holdings beating inflation. However, as the time periods are increased, the gap widens quite considerably, with the likelihood of equities beating inflation reaching 100%, where the investments have been held for a period of 20 years. So, while equity holdings may be riskier in the short term, when viewed against inflation they have offered a higher level of certainty in the long run.

While we cannot truly know what the future holds for deposit rates and investment returns, only investments can provide the potential for real returns to preserve and grow wealth. Any investments should be made in line with an investor’s agreed risk profile, capacity for loss, and need to take risk and, while they should ensure that they have easy access to enough cash reserves should the unlikely happen, holding too much on deposit could potentially be detrimental to meeting longer term financial objectives and priorities.